The following report was written by HAT (Network for Free Education), OHA (University Lecturers’ Network) and HAHA (Students’ Network) to express their common concerns about the Hungarian education reforms to the Hungarian government and the European Union. This report is intended to Rózsa Hoffmann, Hungarian State Secretary for Education, Androulla Vassiliou, Commissioner of the European Commission, the Hungarian Delegation of the European Commission and the European Parliament.

***

According to HAT’s, OHA’s and HAHA’s opinion, the recent laws on higher education, public education and vocational education, along with supplementary governmental decrees, seriously restrict the implementation of the European Union’s core values in Hungary – including the principles of equal opportunity, freedom, legal security and competitiveness.

As a result of the centralization taking place at the institutional level and the newly defined content of the core curriculum, provisions arise that further inequality of opportunity and lower the quality of education. Since these characteristics are coupled with a drastic decrease in allocated resources, Hungarian public education will not be able to meet the labour market’s new challenges and the expectations of the society. There is a significant risk that the general level of education is going to drop and it will not be able to prepare young people for life-long learning; furthermore, it will not succeed in developing key competencies at an adequate level.

Ill-prepared and rushed implementation of simultaneous changes at the level of structure, content and personnel is an aggravating factor in the situation. Institutions, educators and students alike are unable to plan, even for the following year. The centralisation of school ownership by the state (instead of local communities), the enforced and unexpected replacements of headmasters, the implementation of the new structure of educational governance, all take place during the school year – whilst lacking a road-map of necessary details.

The reforms of vocational education deepen social inequalities, challenge equal opportunities and worsen employability by decreasing the amount of time dedicated to general academic and professional subjects, and through over-centralization.

Hasty and unprepared governmental decisions concerning higher education involve unforeseen and very serious funding cuts, together with a generally unpredictable financial policy, making planning impossible. Arbitrary and radical ways of limiting the number of state financed students, crippling certain educational sectors, have all contributed to confusion, insecurity and an alarming atmosphere at universities (both among faculty and leadership). Notable resource cut-offs with unfair and partial redistribution of the remaining resources, together with arbitrarily announced restrictions during the academic year, make the future of students, employees and schools impossible to plan.

Alternatives, such as a graduate tax, funding university attendance through general taxation or the development of a universal and fair tuition-fee system could at least partially solve the financial problems of higher education, although these plans are not even on the agenda. Hungarian higher education needs improvement, quality assurance, and well-founded reforms in order to maintain its position, and improve its international situation. Yet, recent and planned decisions of the government only concentrate on the fiscal balance and some simplistic ideas about an ever-changing job market, instead of a gradual and reasoned long-term improvement and a reasonable structural reform following the best practices available.

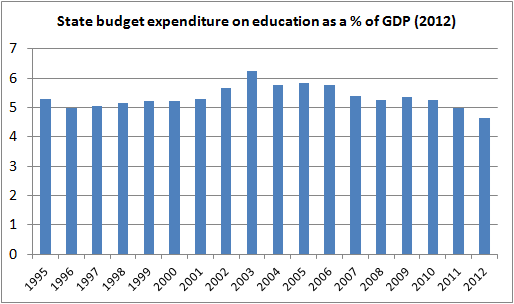

Although the Hungarian financial situation is shaky, the solution cannot be to further decrease the resources for education (it is currently less than 5% of the GDP, well below the EU standards). In this report there is no room for presenting the situation in its complexity. We would suggest, however, that at least some of our country’s financial problems derive from the current government’s so called “unorthodox” economic policy.

The Union’s commitments in the area of the creation of a knowledge-based society, the increase of global economic and technological competitiveness would imply an increase of the financial resources for research and development to 3% of GDP. The Hungarian government made a modest effort in committing itself to the Union’s common plans for Europe 2020: it claimed to increase the expenditures for research and development from 1,16% to 1,8% of GDP.

When compared to the OECD and the EU, expenditures in the fields of education, research and development are considerably lower. The lack of private financing only worsens the situation.

New legislation on public education, vocational and higher education and their supplementary measures do not support the development of a knowledge-based society. Neither does it increase employability, nor serve aims that the Hungarian government adopted in international agreements, to which the Hungarian government has allocated European Union funds, along with other financial resources.

In the field of education the Union does not interfere with the policies of member states. The collectively created laws set rather general aims instead of enforcing the implementation of concrete laws. The EU uses such tools as motivation and persuasion for inducing changes in the member states. The European regulation leaves the decision to the discretion of the national governments – therefore the Hungarian government is using rhetorical means in order to hide the fact that its policy towards public education, vocational education and higher education goes against European values and European development efforts. While qualitative and quantitative development of every level of education plays a key role among the goals of the Union, moreover assurance of equal opportunities is of central importance, the Orbán government does not even consider these aspects. Their regulation of educational policy has the sole purpose to decrease funds available for public education, in the name of certain principles of doubtful merit, such as to empower the ‘middle class’, to administer the educational sector’s political-ideological reform, and to enable centralized governmental control.

The hyperactive law-making of the current two-thirds parliamentary majority, the ad hoc regulation by governmental decrees of key elements that are left out by the drafting of sloppy, ill-considered laws, and the regulatory overload of different governmental institutions make it impossible to plan the future – both for the public, and other stakeholders. The additional fact that the government is not willing to consult with the civil consultative bodies created after the ’89 transition further aggravate the problems. The representatives of various interest groups do not have the possibility to influence decisions.[1] The planning phase, the draft laws and governmental decrees relevant to the fields of education are not discussed prior to implementation, they are not supported by any feasibility studies and are not synchronised with one another.

The relationship between certain levels, institutions and functions of the Hungarian public administration is rather chaotic, too. Policy decisions are not made at their appropriate level, close to the actual processes and having a clear understanding of them, but at the highest possible level. Similarly to other offices of public administration, in the case of the education sector, instead of the principle of subsidiarity, the political centre’s will prevails. Legislation, governmental decrees and governmental plans concerning education subsume professional considerations to the political majority’s aims. Such reforms are designed for the maximalization of the centre’s influence. Every decision ends up being made at the highest level; therefore every stakeholder in the educational field is forced to bargain and lobby in the head office.

As a result, legislation on education, governmental plans and provisions (Law on Public Education, Law on Vocational Education, Law on Higher Education, Széll Kálmán Plan 1-2, Government Program, ENIT[2], NFFI[3], etc.) are not part of a well-founded or synchronized development process. On the contrary, they bear the risk of impoverishing the Hungarian public and higher education – therefore they threaten to reach completely opposite consequences to the EU2020 strategy.

The public administration priorities of the current government are best presented by the budget of 2012, whereas compared to last year, social expenditures decreased by HUF 118 billion (2,4%), healthcare expenditures by 61 billion (4,3%), educational ones by 40 billion (2,9%), and cultural ones by 31 billion (14%). These budget cuts equal 250 billion HUF which amount to an unprecedented reduction of funds in times when the GDP is not decreasing by the same percentages.[4]

The unprecedented budget cuts in the public services will undoubtedly result in crippling the given fields, destroying existing establishments and annihilating their services. The government compensates its unsuccessful economic policy – among other things – by unreasonable and disproportionate budget cuts from the public services. They are placing the costs of state-building, and the concentration of governmental power, upon the public services.[5]

”Since 2006 the governmental support of public education has been decreasing, […] the sector suffered some of its greatest damage in 2012. As of today it has decreased at a lamentable level proportionally to GDP. ”[6]

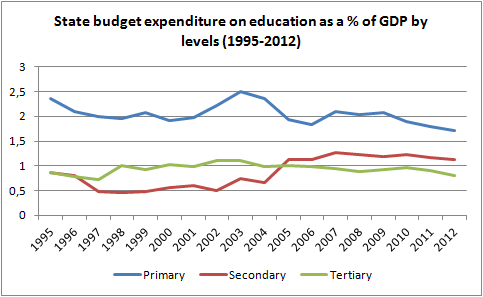

”In the past 10 years the internal proportions of the educational financing have changed to the benefit of secondary education and the disadvantage of higher education – says Péter Radó in his analysis. ”[7]

In our opinion, the current government’s priorities prevent, rather than encourage the realization of the EU2020 plan in Hungary. Among other things, the European Union expects its member states to decrease the number of early school-leavers to below 10% by 2020. The Union’s objective concerning higher education stipulates that at least 40% of citizens of the member states aged 30 to 34 needs to have an advanced degree. In close connection with the education and training system there is the objective to decrease by 20 million the number of those living in depravation and social exclusion, and reduce the number of those at great risk of poverty and social exclusion. The Hungarian government accepted more modest pledges, as compared to the Union’s 2020 plans, whilst governmental decisions of the past few months further hinder their accomplishment.

In the following section we are going to study the probability of realizing the EU2020 commitments in Hungary in three key areas: public education, vocational education and higher education.

Restructuring public education and the EU2020 pledges

Since its rise to power in 2010, the present Hungarian government has been restructuring the entire system of public education, with the passing of a new public education law in parliament.[8] These reforms, however, do not point in the direction of modernising our society and economy. On the contrary, this restructuring is set to prevent Hungarian public education from adapting to principles generally accepted in Europe and the western world. The chances are that, due to these changes, the level of public education will fall in Hungary, modernization tendencies regarding the improvement of key competencies will come to a standstill and Hungary will be unable to cover even the minimum pledges she made in the EU2020 strategy.

During its 11 or 12-year long training, Hungarian public education prepares students to adapt to labour market demands, do further vocational training and gain admission to higher education. In a more general sense, improving key competencies is crucial to preparing students for lifelong learning whilst providing children and young adults with an academic and educational basis necessary to find their place in life. There is a worldwide consensus, including the educational documents of the EU, concerning the function and social tasks of education: much of this focuses upon education as a resource for creating a workforce. Consequently, this report also concentrates on the question of how Hungarian public education will be able to perform the tasks required to develop a modern workforce at the beginning of the 2010s.

Education-related government documents (such as legislative constructs or the law entitled „National Reform Program of Hungary Based on the Széll Kálmán Plan”)[9] give status analyses and mark tasks based on the assessment that there is a significant structural and qualitative discrepancy between labour market demands and training output. Although the report devotes separate chapters to the problems of vocational training and higher education, it is vital to mention here their connection with the real outcomes of the workforce-creating function of the entire educational system. The present government acts upon the ambitions of certain business circles and on its own ideologically distorted, unrealistic concepts, rather than research-based survey data. Measures show a definite fall in the qualification standards. Vocational schools offering a lower level of general, adaptable knowledge are over-proportioned in secondary education, whilst vocational training time has been reduced from 4 to 3 years to decrease the demand for university admission. Changes made, and about to be made, all point in this direction.

Another negative effect on the accomplishment of public educational functions is the planned drop in the number of General Certificate graduates. This trend is narrowing the human resource basis of both higher and post-graduate vocational education, resulting in much worse labour market positions. Thus, the number of people with less adaptable, less mobile knowledge will increase.

The document „National Reform Program of Hungary Based on the Széll Kálmán Plan” also states[10] that the main cause of difficulties in finding jobs for young people is the lack of general knowledge, together with a lack of satisfactory foreign language proficiency. Yet, the changes to be introduced in the system of public education will result in serious problems concerning the improvement of general knowledge, foreign language proficiency and key competencies, which will negatively affect the erudition of future employees.

Hungary is facing grave labour market problems, including one of the lowest employment rates in Europe. To solve these, the government should provide young people with a higher quality, or rather a different type and structure of knowledge and competencies. Complex, long-lasting key competencies would be necessary to prepare young people for lifelong learning. Rhetorically, of course, modern demands about educating future employees are being communicated. Most measures, however, run counter to these. Some of the most important examples are as follows:

Centralizing the system of public education management

With the new public education law, the system of public education management is becoming strictly centralized. Since 1993, the great majority of public institutions have been managed by local governments. These institutions will be taken over by the state from January 1, 2013, with the obligation for local governments to continue financing them. As a result, these institutions will have to face difficulties in carrying out their special, educational, local initiatives in several respects (management, syllabus), as they will have to meet the requirements of the central management. There will be further centralization in vocational training with the concentration of institutions: only one vocational institute per county will be permitted for every 10 000 students. Moreover, this concentrated institute will comprise both vocational and technical schools alike. This means serious offence against the principle of subsidiarity taken for granted in Europe.

Centralization of content regulation

There is going to be significant centralisation of the system for regulating content. As stated by law, institutions may only specify ten percent of the teaching syllabus and the remaining ninety percent of the syllabus is specified by the National Curriculum[11], (in Hungarian: Nemzeti Alaptanterv) which is a centralised curriculum. According to the review of experts the centralised syllabus completely covers the whole school-time of an average school – thereby depriving schools completely of their freedom to specify most areas of their curriculum taking into consideration the demand of their public. It also entails a significant restriction on the freedom of teaching methodology. The application of modern teaching methodology that helps the learning process and gives better results is going to be hampered, because the sheer quantity of previously specified curriculum will effectively force teachers to choose traditional methodology.

The centralization and nationalization of the institutions supporting public education

The government is also carrying out a considerable centralization of other areas related to education. The distribution of textbooks is going to be nationalised, the number of books approved for publication will seriously be cut back, so the existing healthy competition in textbook distribution will be restricted. In order to take governmental control over the organisations supporting education, the Hungarian market in educational services which has been strengthened in recent years and has helped both institutions and teachers, will be practically dissolved.

There were significant changes in the evaluation of institutions and teachers in the past two decades. Quality control, which was based partly on self-assessment, was strengthened. Now the government, instead of reinforcing the previously mentioned method of quality control based on positive tendencies, is setting up a professional supervision system that is bureaucratic and focuses on controlling instead of improvements. The regulation and the working mechanism of professional supervision system are currently unknown.

Changes in the number of early school leavers

The new law reduces compulsory school attendance age range from 18 to 16. In vocational schools the students are going to complete a three-year vocational training instead of a four-year training and their proportion is going to grow among the students participating in secondary education. The reduction of the age limit for schooling is going to raise the proportion of early school leavers. The expansion of vocational schools and the reduction of vocational training time will result in the deterioration in quality of secondary level graduates’ qualifications, contrary to the need for the changes stated in EU2020 strategy. It is highly possible that Hungary will not be able to meet its commitments to reduce the number of early school leavers to less than ten percent.

Fairness, equal opportunities

Citizens with low levels of education are a determining factor in the disability to meet the demands of the labour market and to decrease unemployment. The low rate of employment in Hungary may be partially traced back to the fact that people with the lowest level of education are less capable of adapting to changes; thus the unemployment rate among them is high. This problem may be solved partially by the creation of workplaces that enable their employment. In the long run, it is equally, if not more important, to increase the levels of qualification and education. At school, students with the weakest results come from a socially disadvantaged stratum of society. Therefore, policies that aim the reduction of social inequalities would have great significance in improving education. However, the legal and political terms of the new regulations on education will not reduce social inequalities and will menace the results achieved in the previous decades. Primarily, the reasons for this are the following:

- The public education law, relative to the former relevant legislation, has taken a significant step backward in regard to equal opportunity guarantees.

- It no longer contains guarantees for the elimination of latent or manifest discrimination, or of segregation. In particular, it does not include sanctions for the violation of the anti-segregation rules, according to the anti-discrimination law, as modified in 2011. The law does not provide an opportunity to eliminate segregated education, which affects approximately a third of Roma schoolchildren.

- Several regulations result in the growth of unequal chances as a “side effect”.

- Certain regulations within the law punish precisely those students who are already in the most vulnerable position. They are deprived of important rights and opportunities that were provided under the previous law. Their position is fundamentally worsening, due to the narrowing of educational opportunities.

- Although the law does not prevent inclusion – meaning the integrated education of schoolchildren belonging to underprivileged groups – nor does it guarantee it.

The situation of children with special needs

As the position of children with special needs is of paramount concern to society, it has played a key role in the debate preceding the enactment of the public education law. The resulting law, however, represents a drastic step backwards in terms of both attitudes toward segregation and the actual law itself. Progress toward a truly integrated environment has been sacrificed due to financial and human resource constraints. “Cold integration” – the process of integration without comprehensive support – is currently on the rise, ultimately degrading the political and social support for inclusion. This trend is accompanied by a growing intolerance towards “being different” in Hungarian society. Disabled children are increasingly isolated from society, and their chances of adaptation are diminishing. Furthermore, the reputation of institutions that continue to undertake a policy of inclusion has been negatively impacted. Achievements and innovations of the past have been allowed to atrophy.

The impact of changes in public education on the number of university graduates

As a result of the change in the proportion of secondary school students who are adequately prepared to continue their studies, Hungary risks non-adherence to the EU2020 strategy. According to the country’s plan, 30 percent of the population between the ages of 30 and 34 must have a university degree by 2020. Even if this proportion can be reached by this time, however, there remains a danger that the combined effects of the new public education law and decreased funding for higher education over this period will see the proportion of those having a university degree decline again after 2020.

The impact of the deterioration of cultural institutions on education

Financial constraints, the disorderly system of ownership and maintenance, the withdrawal of tasks in the related rules, as well as the insertion of ideological preferences in the decision-making process significantly degrade the standard of working conditions. These issues have a particularly strong impact in the countryside, in villages, in small towns, and in specific institutions (such as museums and public collections). The professional level of the services offered at these institutions which are forced to increase their income, has therefore decreased. Access to services connected to children is now determined by the financial situation of the family, rather than by the needs of the child. Opportunities for schools and cultural institutions to educate the public have likewise diminished.

This deterioration has been most harmful to the so-called “general cultural centres”. These are multifunctional, integrated, complex public educational institutions, modelled on similar institutions in the West. Since they were first established in the 1970’s, general cultural centres have spread throughout Hungary. There are approximately 200 to 300 such institutions in the country. The mere survival of these centres – devoted to life-long learning and often of notable architectural worth – is now in question. Radical changes in ownership have left these institutions in a hopeless situation. Three disparate types of ownership for educational establishments have made it impossible to create a functioning institution within the present legal system. While educational services have been taken over by the state, nursery schools remain under local government ownership, and culture centres have been exposed to the economic reality. Due to these circumstances, these centres and their value to society may disappear from the stage of Hungarian culture and education.

Vocational reform and EU2020 pledges

Vocational training in the educational system and options for employment

The fact that the presentation of vocational reform is contained within the employment chapter of EURO 2020 objectives well reflects the approach of the entire reform: vocational training has to be based on current economic aspects, whilst educational considerations are of secondary importance.

The introduction to ‘Széll Kálmán Plan 2.0’ states: “Changes concerning vocational training are being made to adapt the overall training structure to economic demands as regards the course of training and the rate of workforce, the main objective being to provide young people with competitive skills.”[12]

In fact, the current measures make no attempt at either increasing employment or providing young people with competitive skills. The reform takes due care of criticism by the Chamber of Commerce and Industry of the present system of vocational training.[13] This criticism aims to improve levels of instantly profitable, market-based skills by decreasing the amount of general knowledge, whilst increasing the amount of practical knowledge in the curriculum.[14]

The idea of „meeting economic demands by vocational training” had been conceived by the preceding socialist-liberal government. As early as in 2009, an amendment to the public education law introduced an alternative course, allowing a so-called 3-year pre-training to be initiated after primary education, thus offering immediate scope to learn a given trade. The 2011 Law of Public Education only makes this form of vocational training a general practice. Besides, it leaves no doubt that vocational schools may include general knowledge in their curricula only to the extent directly required by the skills necessary for the given trade.[15]

There had yet been another option offered to economic actors by the previous government – to be members in the so-called Committees for Regional Development and Training, and determine which vocational trends should be financed by the state. The only change made by the 2011 Vocational Law was to replace regional with county levels and that each county committee now has the right to move a resolution for the government, which is to decree ”the circle of vocational and technical training per county, which entitle the respective vocational school to receive budget contribution.”[16]

Since 2010 scholarships have been granted in the field of so-called “trades in demand” – demand in the wider economy. This approach is ineffective in the short and long run alike.

Vocational schools ought to prepare students for 50 years of life in the labour market. Apart from learning a given trade, young people should have the opportunity to attain eminent key competencies irrespective of trade, as well as the flexibility required to follow up new trends in their trade, including change of vocation. This objective is definitely not provided by decreasing training time to 3 years (down from 4 years), and limiting the chance to study anything else besides strictly professional competencies: the new and obligatory central syllabus proposes less than 25% of teaching time for general knowledge, excluding P.E.

Recent studies have clearly proven that the restriction of obtainable/financeable vocational qualifications in schools of a certain region does not serve even the short-term interests of economy.[17] It is impossible to accurately determine which trades will be in demand 3 to 5 years ahead. In addition, county-based planning does not meet the requirements of mobility. Furthermore, the high rate of people quitting their career should be taken into consideration: as early as the first few years after graduation the majority of graduates search for a job entirely different from their original qualification. This raises questions about the effectiveness of the financial motivation of young people studying trades-in-demand and justifies the efforts to endow skilled workers with competencies to be used far beyond their own trade.

Statistical analyses have also shown that the rate of unemployment is just slightly lower among ‘trades-in-demand’ than the average of people with similar qualifications. The lack of key competencies hinders career prospects among those with “good vocational qualifications”. In contrast, those who study their chosen trade with pleasure will possess skills that preserve their market value even if they fail to find employment in their trade.[18]

Another obstacle impeding adaptation to the demands of economy is the fact that obligatory central curricula are imposed on vocational training, as well. Schools are allowed to apply no more than 10% of their own initiatives. This limitation deprives schools of the chance to consider local needs, including those of large local enterprises, which aggravates attempts at monitoring innovations in training.

Apart from the tenor of vocational training, the reform aims at increasing the proportion of students in vocational training to the detriment of those attending comprehensive schools. The government expects this to increase employment rates. However, unemployment statistics do not support the advantage of vocational training as opposed to academic education (resulting in a General Certificate). High school graduates have a far better unemployment rate than those graduating from vocational schools.[19]

The reform emphasizes that vocational graduates are provided with the opportunity to obtain a regular high school diploma within two years. The low level (max. 33%) of general education in these schools makes this practically impossible, since students receive one year of general knowledge during their three-year training. To make matters worse, even this is not based on the National Syllabus, the frame of the newly-centralised secondary curriculum.

The other branch of vocational training – technical school – is less affected by the reforms, though the trend is similar. The proportion of general education will likewise decrease. It is stated that the kind of training provided is not to prepare people for higher education in other than specialized faculties, a tendency going against present-day practice. The rigid central curriculum is likely to render it impossible to prepare students for an easily adaptable perspective on the local labour market, regardless of the post-graduate vocational year offered by this “branch.”

Vocational training in technical schools will be deprived of higher vocational education. Such 2-year training programmes were provided by both secondary and higher educational institutions. After 2013 it will be reduced to universities alone. Research has proven that only a smaller percentage of graduates of such university courses can find employment (partly for reasons of there being little practical training, partly for being encouraged by the university to further continue their studies[20]). The initiative is therefore not explicable in relation to its effect on the labour market. Instead, the report seems to boast the formal fulfilment of EU2020 indications: most students will graduate from higher rather than post-secondary education.

All in all, we must refute the claim that vocational reform will improve employment. The modern concept of improving employment[21] is based on competencies rather that qualifications. This reform introduces a negative approach towards attaining economically-favoured competencies.

Both the Széll Kálmán Plan and the Vocational Law emphasize career orientation. This emphasis may be correct, but until the official enactment of this law it is still doubtful whether it is going to aim for orientation towards economically significant careers, or rather to obtain career-building competencies and to help making decisions. The first option seems to be supported by the fact that the Hungarian Chamber of Commerce and Industry will play an important role in the second phase of the so-called TÁMOP 2.2.2. Project (whose objective is to improve career orientation).

Lifelong vocational training and employment

The correlation between employment and vocational training may be examined from the aspect of lifelong vocational training.

The government-backed vocational concept recommends school-like or school-based lifelong vocational training for adults. There is, however, a positive trend in this field: part-time (evening and correspondent) training will become free, besides full-time training as regards the attainment of the first vocational qualification. Still, the question remains: how real this choice will be, will the government finance a sufficient number of classes to meet this demand?

The preference for schools and higher education to provide lifelong vocational training mainly suits centralizing tendencies and does not serve the basic interests of lifelong training. Companies involved in training are usually more flexible than schools, thus can adapt faster to market needs and can take varying student abilities into consideration. Quality assurance and consumer protection are equally important but may be achieved in a different way.

The abrogation of module-type exams limits the opportunities of lifelong vocational training. Complex exams make it impossible to accept previous exam results in studying new vocations. The new National Training Register, about to be published, also restricts the area of obtainable vocations in lifelong training.

Temporary market demands ought not to be met by scholastic but lifelong vocational training. This has performed poorly until now and the future possibilities are feared to be narrowing. Enterprises will certainly cut back on encouraging their own employees to continue their training as these costs will not reduce the amount of compulsory vocational contribution they are to pay for the government.[22] In contrast with the growing number of supported, labour market-conscious trainings, indicated by the report, nothing has happened so far.

Vocational reform and early school dropouts

One of the chief objectives of EU2020 is reducing the number of early school dropouts. With this reform, the number of students leaving school without a proper vocation and GCE will increase rather than decrease, as is erroneously maintained by Széll Kálmán Plan 2.0. No sufficient evidence has been gathered that 9th-year vocational school dropouts are highly represented in the statistics because of the lack of traditional vocational training. Those with poor elementary achievement become dropouts in the so-called pre-vocational training, as well. This trend can only be stopped by introducing innovative methods and employing expert mentoring assistants. Széll Kálmán Plan 2.0 takes a few steps in this direction but practice has shown that innovations are struggling for survival in the lack of government support and individual treatment is discouraged by centralizing efforts. One thing, however, is obvious: reducing the minimum age of compulsory education to 16 years of age will surely increase the number of people leaving school without having obtained a proper vocation.

Restructuring higher education and the EU2020 pledges

The announced and leaked government action plans of 2012 make the impression that instead of improving higher education both in quality and quantity, the Hungarian government has taken the direction which leads to regression and atrophy. With the EU pledges concerning the number of citizens with higher education, the Hungarian government has taken no risk, as the consequences of the current reform of higher education will only show after 2020. Instead of a trend of development, expected by the EU, the number of students and graduates will significantly decrease compared to the current level.

The decrease in the number of state sponsored students, the radically increased tuition fee, the student contracts which restrict the freedom of movement and employment and the student loan schemes which entail long indebtedness, all make the participation in higher education inaccessible and untenable for a notable portion of the younger generations. The lack of a fair tuition fee system and student grant system makes the situation of young people even harder.

According to the principle of “divide et impera”, the massive cuts in funding and rumours about radical restructuring – which would cause the termination or merging of some institutions – have shaken the whole sector of higher education, turning the actors of the different institutions and regions against each other. All of these changes have been introduced by the government without feasibility and impact studies and without formal consultation with experts, trade unions or other organisations of academic staff.

Changes in the number of university graduates

Compared to the plans about higher education in EU2020, the Hungarian pledges are minimalist. The EU plans to raise the proportion of university graduates to 40% in the 30-34 age group. Hungary settles for raising this rate to 30,3% from 25,7% of 2010 (out of this, a 30,7% rate of graduates among women was already accomplished by 2010). This pledge means no challenge at all, it can already be regarded as accomplished, as the affected generation is already enrolled to higher education and likely to graduate. (On the other hand, it indicates the government’s cynical attitude to EU targets very well.)

The current actions of the government (radical cuts in funding and in the number of state sponsored students, and the merging of institutions) are based on the false assumption that there is over-education at university level in Hungary. Contrary to this popular belief, the charts of OECD “Education at a Glance 2010” – see below – show, that the proportion of graduates in the Hungarian population is smaller than OECD or EU average, and moving from the older to the younger generations, this difference gets more significant.[23]

| Rate of graduates in different age groups (% of age group) | ||||

| 55-64 | 45-54 | 35-44 | 25-34 | |

| OECD states | 20 | 25 | 29 | 35 |

| EU member states | 18 | 22 | 27 | 32 |

| Hungary | 16 | 17 | 19 | 24 |

| Hungary’s lag | 2-4 | 5-8 | 8-10 | 8-11 |

Source: Education at a Glance, 2010

Comparing Hungarian and international data one can argue that participation in higher education is too low in Hungary, and government measurements will further decrease it in the future.

The fact that the freshly graduated find jobs in Hungary in an average of 2,4 months also contradicts the false belief concerning over-education – as shown in the next table below:[24]

| Training field | Net salary (% of career starters’ average net salary) | Employment rate (%) | Duration of finding a job |

| Agriculture | 88 | 86,4 | 3,1 |

| Humanities | 88 | 81,9 | 2,5 |

| Economics | 117 | 88,0 | 2,1 |

| IT | 114 | 88,6 | 2,4 |

| Law, administration | 112 | 87,4 | 2,1 |

| Technology | 107 | 85,9 | 2,5 |

| Medical | 89 | 86,7 | 1,9 |

| Teaching | 82 | 83,2 | 2,6 |

| Social science | 92 | 86,4 | 2,2 |

| Science | 86 | 72,1 | 4,2 |

| Together | 100 | 85,5 | 2,4 |

Salary, employment rate and duration of finding a job of career starter graduates in 2010, (based on Career Monitoring of Graduates, 2010)

Another false surmise, namely that unemployment rates are high among graduates, is also widespread. The government program also asserts that “currently, there is no market demand for half of the diplomas that can be earned in higher education.” In fact, the opposite is true: among the groups of graduates of different school levels, university graduates’ rate in unemployment is the lowest. Statistics clearly show that unemployment rates and long time unemployment are the highest in the group of the undereducated and early school leavers. Life conditions of graduates are better too: they earn twice as much as those without a diploma and their chance to find employment is five times higher.

Government propaganda – backed by a mock public consultation process called “social consultation”[25] – has strengthened some widely shared false assumptions. It has suggested, among other things, that the state sponsored training of lawyers, economists, experts of social sciences and humanities is merely a waste of money, that it is the best way to increase unemployment. On the other hand, it falsely pictures the government’s higher education policy as being in favour of necessary and viable training forms and neglecting the useless ones.

In fact, however, “due to the changes [in higher education policy] a field of knowledge is supported by the state more strongly

- the more expensive training is in the field;

- the less graduates from the field will earn;

- the worst outlooks graduates from the field have to be employed;

- the later they are able to find a job.” [26]

To be able to understand the higher education reform currently in progress, it is important to consider the intention of the government to favour a specific social group: “in accordance with the vision of renewal in higher education initiated in 2011, the reform outlined in this document also aims to increase the Hungarian national middle class and the highly qualified, open-minded intelligentsia, both in quality and quantity…”[27] “Hungarian national middle class” refers to a group which, as for wealth, social and political position, is already in a hegemonic position, and for which the current political elite wants to guarantee further advantages, while making access to higher education immensely difficult for underprivileged youngsters. These measures will notably slow down social mobility and infringe the basic EU principle of equal opportunities.

The relation of higher education and the job market

The current government is continuously proclaiming its aspiration to form education, especially higher education, in accordance with the alleged needs of the job market. The government has cut state sponsored places in higher education to an extent never seen before, giving priority to IT, mechanics and science at the expense of law, economics, social studies and the humanities. All this is being done without impact studies, expert analyses, and only vaguely referring to alleged figures of the job market. Many experts and actors in the job market unanimously claim that the job market cannot predict labour demand accurately, because it changes according to long-term trends, influenced by numerous factors, and thus it cannot be controlled manually. The government intends to bestow a disproportionately large power on representatives of the job market both in the FTT[28] and in restructuring the system of higher education institutions. Neither the ministry, nor the representatives of the job market dispose of trustworthy information on job market demands. These demands are only reflected reliably in incomes, the duration of finding a job and employment rates.

The government’s measures also seem to ignore the general principle based on long-term observations and measurements that the spread of higher school education in society helps development, competitiveness and economic and technological advancement, and at the same time has a beneficial effect on consumption (e.g. cultural consumption, tourism, consumption of electronic and IT devices). In the post-industrial socio-economic environment the role of knowledge has grown greatly, more and more knowledge and increasingly higher competencies are needed. As secondary education became widespread in the 20th century, passing down general knowledge increasingly becomes the task of higher education. Global economy, technological improvement and accelerating innovation have changed the job market: instead of former demand for industrial labour; services and dematerialized work have gained more significance, which require more highly qualified workforce. Knowledge-based society cannot be created through the regression of education, rather through encouraging new generations to enter higher education and earn knowledge and skills. There is a strong correlation between the quality and quantity of education and economic growth. Yet, the measures introduced by the Hungarian government are likely to lead to less and worse higher education contradicting international trends and EU development plans.

The new system of public funding in higher education and its consequences

As in previous years, the budgetary support of higher education in Hungary has decreased again this year, and will continue to decline in the following years. “According to the Széll Kálmán Plan, within the system of state supports both the state grant / partial grant for students and the direct financial support of institutions will be reduced in the medium term.”[29]

The government removed the issue of financing higher education from the Higher Education Law; nevertheless, the relevant governmental decree has still not been introduced. In the meantime, the documents made public by the ministry show, that the proposed allocation of resources will neither be based on quality, nor on competition, but on an ad hoc selection by the government.

Up to now the only information available on the new funding system is that financing higher education will rest on three pillars (including students’ grants, distribution of development funds and appreciation of excellence), but in all three, almost exclusively, the government’s will prevails. This can well be seen by the fact that the NFFI draft declares that the status of excellence will be bestowed “based on objective indicators”, however, the chart showing the Hungarian universities’ ranking does not even list the new National University of Public Service, while the government plans to ensure an exceptional status and exceptionally comfortable funding, arguing that "the National University of Public Service is the only university that offers public administration, law enforcement and military studies at a nation-wide level.”[30]

As for development funds, the government is not likely to encourage fair competition between higher education institutions. Priority will be given to universities hand-selected by the government: “… development plans of institutions whose strategic objectives are in line with those of the sector, will receive greater budgetary and developmental, support”[31]., while these objectives are not defined.

In the allocation of resources the newly established “higher education development poles” will obviously have a key role. In the lack of clear development objectives, the government will prefer certain institutions and certain institutional development plans, while others will be neglected. The funding of all governmentally non-favoured activities is cynically relegated to the realm of institutional autonomy: "Development profiles set as a priority will be given a prominent role both in the FFP budgetary and EU support and in the policy decisions of the government. In other areas, that are not treated as a priority by the state, public higher education institutions may run developments in the manner designed by the IFT [Institutional Development Plan], as autonomous institutions.”[32]

The relationship between institutions assigned to each and the same pole is unclear, just like the degree of their integration. There is a risk that the allocation of resources to poles will lead to conflict between arbitrarily merged institutions, causing unnecessary squabble among them and informal haggling for benefits directly with the government. The arbitrary cuts in admission numbers, the raising of tuition fees, and the system of new higher education poles make the future of certain institutions highly dubious and may result in small regions’ losing their only university, thus increase social-regional inequalities and lessen the chances of breaking out.

Cuts in the number of state sponsored students

The radical and ad-hoc cuts in the number of state sponsored students in higher education and the significant increase of tuition-fees do not take into consideration the demands of the economy, nor students’ career plans, and seriously shatter higher education institutions.

These measurements heavily affect the chances of young generations to enter higher education. Youngsters from disadvantaged social conditions will be locked out from higher education, a trend further favouring young people of higher social-economic status. Surveys in sociology of education show that the effect of social structure on admission and pick of subject is already way too strong in Hungary. The plans of the government to further decrease the number of state sponsored students in the coming years, make the implementation of the principle of equal opportunity impossible, restrain social mobility and contribute to the division of society. The introduction of three forms of student finance suggested by the Government (i.e. state sponsored, partly sponsored, self sponsored) makes higher education inaccessible for deprived children that will lead to growing social disparities.

The radical change and late announcement of state sponsored student numbers (the numbers were announced two weeks before the application deadline in 2012) crushed down on students’ career plans and discouraged many of them from application. According to figures published in spring 2012, the number of applicants to higher education decreased by 22%, i.e. 31 thousands students, in the running year.[33] The cuts in state sponsored places will mostly affect girls and those living in Budapest.[34]

Tuition fees for self sponsored students in different fields of study are very high in international comparison, and are especially disproportionately high compared to GDP per capita or to the average income in Hungary.

Institutions disfavoured in the distribution of state sponsored places are forced to ask for high tuition fees, which is likely to lead to a decreasing number of applications. This can cause the perishing of fields of study, departments, faculties and even institutions – not as an effect of real competition, rather of arbitrary central decisions. “The number of students may considerably be decreased at institutes which – because of the centralized and arbitrary distribution of the high tuition fees and state sponsored places – can hardly fill in their capacities with state sponsored students.[35] Thus “even some old, prestigious universities offering highly regarded degrees may not survive”[36].

To help students with exceptionally increased tuition fees, the government decided to introduce a new student loan construction. According to experts’ calculations, “Student Loan 2” will lead to unmanageable debt of students[37] on the one hand and a steep increase of state debt[38] on the other (as according to the government decree, part of the high interest rates of the Student Loan 2 will be paid by the state budget).

The State withdrew HUF 34 billion from higher education institutions in 2012, that is to say, they will receive 17% less than they had in the budget of last year.[39] What is more, the Government distributed the support arbitrarily. “In the new system certain institutions and fields of study will continue enjoying advantages, while others will be sentenced to death, or, in a better case, to a long agony. The reduced sum will be distributed among higher education institutions in an arbitrary and unpredictable manner”[40].

In the same way, state financed student numbers, as well as the numbers of self-financing students is allocated arbitrarily. According to the Directives of the National Development Plan for Higher Education (NFFI), through the admission procedure in 2012, the government “will direct ca. 70% of state sponsored students to informatics, technical and natural sciences” (in 2011 this rate was only 48%).[41]

The Government Decree that defined the admission figures arbitrarily and only two weeks before the deadline of application gives reason for serious concern – according to several departments of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences. The Department of Economy and Jurisprudence and the Department of Philosophy and History issued a joint statement: “Feeling responsible for the generations entering higher education, we are deeply concerned by the drastic cuts in state sponsored student numbers in law, economics, social studies and the humanities. In the interests of professional culture, so significant in Hungary’s future, in the interest of new generations of intelligentsia and freedom of career planning we suggest that decision makers should increase the number of state sponsored students in law, economics, social studies and the humanities as soon as possible, thus putting the principle of economic and social effectiveness into effect.”[42]

The Department of Philosophy and History, in their letter sent to the President of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences on January 27th, 2012, declared that “providing advantages to the technical and natural sciences within the decreased number of state sponsored students will be dysfunctional, if it forces students to pick subjects whose requirements they cannot and are not motivated to meet.” In the same document, academicians state that the Government Decree mentioned above “without the examination of social conditions, starts out from the unfounded hypothesis that the graduates in the humanities (despite their erudition and commitment, their command of languages and communication skills, their social sensitivity and effectiveness) do not find jobs in the developing market economy”.

The claims articulated by the Academicians at the beginning of the year have remained unfulfilled desires. From the background document “Directives of the National Development Plan for Higher Education” published at the end of April 2012, it turns out that the Government sticks to the original plans, and decided to introduce even more centralized manual control: “central distribution of student numbers, defined for each institution”; “…the Minister responsible for education, distributes state sponsored places among institutions – and subjects, if necessary -, taking into consideration decision-preparation procedures and content issues as defined in the Law.”[43]

In our view, young generations’ career choices should not be influenced by power tools and ad-hoc government decisions, rather by high standard primary and secondary education applying up-to-date knowledge and teaching tools, by skilled teachers open to new scientific and cultural achievements, and by a wide range of educational content and forms attractive and motivating for young people.

Violation of students’ rights

Education plans of several thousands of students were crushed by the late announcement of admission numbers, the radical cut in state sponsored places and the massive increase of tuition fees only two weeks before the deadline for application.

The rights of students in state sponsored education have also been severely violated by the so-called “student contract”, which obliges them to work in Hungary for a period twice as long as the time spent in higher education. This is in contradiction with the principle of free movement of labour, as stated in the Lisbon Treaty, which raises human rights issues as well. This is all the more questionable because it sets requirements for graduates with no guarantee to provide them with job opportunities.

In response to the enquiry by the National Conference of Students’ Self-governments, Ombudsman Máté Szabó stated that the government’s decree disproportionately restricts students’ rights for autonomy and free choice of job and career. Consequently he has asked the Constitutional Court for an opinion and for the suspension of the government decree from coming into effect.

One of the most serious results of measures taken by the Hungarian government is the massive increase of the number of high school graduates who instead of applying for a place in Hungarian universities have chosen to leave the country. In some secondary schools their rate is as high as 25-30%. Mobility of young people is in itself to be welcomed, but if mobility is motivated by avoiding high tuition fees or student contract, it does not serve Hungary’s interest.

Higher education policy counteracts the Roma strategy

Due to the decrease of the number of students admitted into higher education and the financial restrictions, the Roma strategy, worked out and accepted during Hungary’s EU presidency, is becoming unfeasible. Hungarian sociological studies point out the increasing deprivation of the Roma population: they leave school much earlier than the majority population, which affects their labour market position badly. Several government acts ( e.g. setting 16 as compulsory school attendance age limit, the expansion of vocational schools) also work against equal opportunities and make it impossible for young Romas, whose economic, cultural and social conditions are in several respects disadvantageous, to gain admission to higher education. One way for the government to assist the improvement of Roma integration and social acceptance would be to help form a Roma intelligentsia. As the present higher educational measures take an opposite direction, the lack of Roma intelligentsia will prevail.

____________________________________

[1] The situation is best characterized by the lack of mention or allusion of any consultative body in the national core curriculum. If such bodies are created at all, their composition and functioning are determined by governmental decrees.

[2] Tájékoztató az Európa 2020 nemzeti intézkedési terv előkészítéséről, a nemzeti vállalások javasolt értekeiről és az azokat megalapozó intézkedési javaslatokról. [National Plan of Provisions] Nemzetgazdasági Minisztérium, 2010.

[3] Nemzeti Felsőoktatás Fejlesztési Irányai (NFFI) [Directives of the National Development Plan for Higher Education]

[4] Radó, Péter: Az Orbán-kormány közfinanszírozási prioritásairól (A második Széll Kálmán terv elé)

[5] ibid.

[6] ibid.

[7] ibid.

[8] CXC Law of Public Education 2011. Magyar Közlöny, No. 162. 2011.

[9] National Reform Programme of Hungary Based on the Széll Kálmán Plan. Government of the Republic of Hungary, Budapest, 2011.

[10] Op. cit., p. 13

[11] 110/2012. (VI.4.) Governmental regulation of issuing, implementing and application of a National Curriculum.

[12] Op. cit.

[13] At present the general vocational training consists of 2 years of general education giving both theoretical and practical training, followed by a 1 to 3 year-long professional training. Besides these, there is vocational training in technical schools: here general education takes 4 years, followed by 1 or 2 years of professional training (to be opted for with a high school diploma as well).

[14] A Magyar Kereskedelmi és Iparkamara Középtávú Szakképzési Stratégiája 2005-2013; A gazdaság és a köztestületi gazdasági kamarai rendszer megnövekedett szerepvállalásának lehetőségei egy munkaerőpiaci irányultságú szakképzés rendszer kialakításában Magyarországon, 2009.

[15] CXC Law of Public Education 2011. §13 (1): „Vocational schools have ….three years of vocational training, comprising general education necessary to acquire the right qualification plus theoretical and practical education to acquire professional skills.”

[16] CLXXXVII Law of Vocational Training, Chapter 49.

[17] Juhász – Juhász – Borbély-Pecze: Munkaerőhiány és kínálati többlet azonos szakképesítéssel rendelkezők körében: a szakképzés lehetőségei. OFA research, Panta Rhei Bt. 2009.

[18] Mártonfi, György: Hiányszakmák. Educatio 2011/3; Hiányszakmák diadalútja. Szaktudósító 2012 February.

[19] from Central Statistical Bureau database: 9 and 12 % http://www.ksh.hu/stadat_eves_2_1

[20] Györgyi, Zoltán: A felsőfokú szakképzés és a munkaerőpiac. In: Kozma, Tamás – Perjés, István (eds): Új kutatások a neveléstudományokban, Budapest: Magyar Tudományos Akadémia Pedagógiai Bizottsága, 2008.

[21] OECD competency strategy:

http://www.oecd.org/document/6/0,3746,en_2649_37455_47414086_1_1_1_37455,00.html

[22] 2011/CLV law on vocational contribution and on the support to improve training.

[23] Berlinger, Edina: Vödör a fejre. Magyar Narancs 2011/42.

[24] Varga, Júlia: A jövő mérnökei. Magyar Narancs, 2012/01, p. 19.

[25] http://szocialiskonzultacio.kormany.hu/download/1/24/00000/szocialis_konzultacio_kerdoiv.pdf

[26] Berlinger, Edina: Helyre igazítás. Magyar Narancs 2012/19, p. 14.

[27] NFFI, p.3. (see footnote 3)

[28] Felsőoktatási Tervezési Tanács, Council for Planning Higher Education – a body mainly responsible for the development of higher education

[29] NFFI p. 21.

[30] NFFI p. 44.

[31] ibid.

[32] NFFI p. 30

[33] While the number of applicants to state sponsored places decreased by 35 thousand, for the self funded places there were only 4 thousand more applicants. C.f. Berlinger, Edina: Helyre igazítás, Magyar Narancs, 2012/19.

[34] ibid.

[35] c.f. http://www.szuveren.hu/vendeglap/semjen-andras/tandij-aldas-vagy-atok

[36] ibid.

[37] c.f. http://magyarnarancs.hu/publicisztika/felsooktatas-eletre-halalra-78647

[38] c.f http://privatbankar.hu/makro/nemethne-kiszamolta-a-koltsegvetest-veszelyezteti-a-diakhitel-2-246421

[39] c.f http://magyarnarancs.hu/publicisztika/felsooktatas-eletre-halalra-78647

[40] ibid.

[41] NFFI, p. 8

[42] c.f. http://mta.hu/ix_osztaly_hirei/allasfoglalas-a-human-felsooktatasi-teruleten-hozott-fejlesztespolitikai-dontesekrol-129368/

[43] NFFI, p. 20